[By Seun Onigbinde]

When the former head of the Burkina Faso junta, Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, stated that loud gunshots around the Presidential Palace were because of mood swings of soldiers, I felt the comic relief could benefit the creative artistry of the viral jester, Investor Sabinus. In the next few hours, Paul-Henri would lead no government after the unfortunate statement. Burkina Faso has witnessed two coups within nine months. The new leader — Captain Ibrahim Traore — just 34 years old — is a grim reminder of what Nigeria used to be in the mid-1960s. After Blaise Compaore was removed from office in 2014, Burkina Faso flirted with six transitional leaders until Roch Marc Christian Kaboré was elected in December 2015. He was deposed in January 2022 with the usual bombast from coup plotters and those who removed him in January were taken out in September, with the same quip — the failure to curb insurgency.

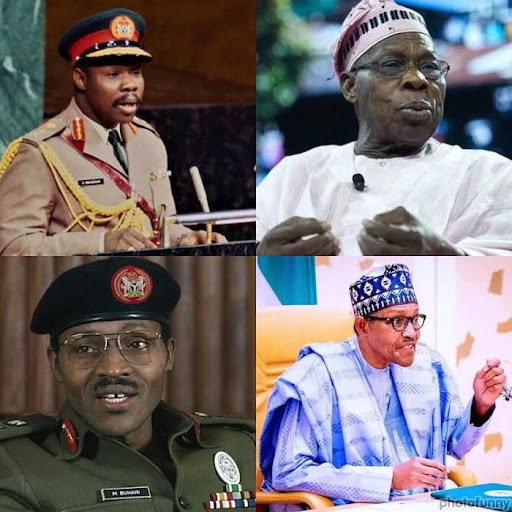

After running in circles since independence, oscillating between khaki and agbada, Nigerians have primarily agreed that we are stuck with democracy and there’s no shred of the military putsch in our national psyche. What changed?

This brings me to a conversation with a friend who moaned about the terrible nature of Obasanjo’s government. With Odi and Zaki Biam, I know that the government did not smell roses, but why the acerbic opprobrium? She mentioned that her father was a young officer in the military, possibly of the Lieutenant-Colonel level, and was removed by Obasanjo’s blanket purge that all military officers (93 officers in total) with previous political posts or who served in military cabinets at any level should proceed on retirement. It was a rug pull that ended the careers of many fine officers. However, what were the choices of General Obasanjo? Pragmatists would have said why not sack the generals, from the Major-General rank and above? Incrementalists would have said why not those who served as Governors, Senior Ministers and a sprinkling of barrack commanders if we plot our history with influential figures in previous coups? Well, would that have cured the situation? The grumbling when Obasanjo travelled incessantly around the world (in his first term) might have landed us back in a military regime and scuttled another republic. The people might have cheered it as they did in Burkina Faso, lured into the dream of another khaki-wearing messiah. However, for military officers who have tasted power and its trappings, nothing else could have appeased them. Crushing future military uprisings needed a surgical removal from the system, an act of revolution in itself.

I wrote this piece after patiently listening to Sam Amadi’s presentation at The Platform, a bi-annual space of thought leadership (organised by my church) that sought answers on the kind of leadership that we actually need. Sam mentioned path dependence, describing how a nation was bound to continue in its chosen path of ruin unless it took on nothing short of a revolution. He asked a simple question, “How many nations have actually significantly changed their story since the beginning of this century?”

How much incrementalism or gradualism can actually fix Nigeria? This is a system with glaring ethical challenges but we think we don’t need anything short of a tear-down. We need to ask ourselves pertinent questions. Would our expensive electoral system provide us with quality leadership that would fix Nigeria? Would the civil service cast in an extractive mindset offer meritorious capabilities that can end our challenges? Would a neo-feudal or patriarchal system ever offer us the Nigeria that we dream of? Would our constitution that promotes sharing oil rent and centrally-allocated taxes offer us competitive states? As Sam Amadi stated, “Nigeria is a country that avoids hard questions, existential ones.”

In a system that costs an enormous fortune to get in and everyone is trying to secure a share, how many Powerpoint presentations or gallons of coffee would be enough? When you see the agony of young educated Nigerians who seek other alternatives from the extractive culture advanced by the leading political parties, it is because they understand that nothing glorious adds up in our journey. The bits and pieces would never be enough. That is why a government can fail in education, health, security, and economy but offer leveraged infrastructure and we accept the bar as high enough. A public governance culture that prioritises the expediency of personal benefits cannot run all our “trains” at once and move us to our destination. This is why 2023 won’t be different if we elect a leader that does not offer a moral example of rectitude in public service, nor possess the courage and capacity to prioritise a clean-up of institutions. General Obasanjo understood this as a soldier and did it without equivocation in the military shake-up.

We can make the prescriptions, offer aid, borrow money, raise tax rates, print more or even receive investments, but the question would always lie in, what’s the culture that pervades the public sphere? What values do we glamorise as a people? If it is about “even if he’s a thief, he’s our own thief” culture, then life-changing service delivery is not what we seek, we are just content with tribalism that fulfils our daily needs. Do we choose leaders that see public service as stewardship and not just another extension of their private enterprise?

Some years ago, I was forced to change the culture of BudgIT to reduce my influence while I applied myself to other things. It came with a lot of resistance and there were even mistakes on my part. I did not lose sight of gauging interest in the systemic changes we were about to make; if anyone was not willing, exit doors were favourably open. It was not easy. It was painful. But that’s what a society that seeks change needs to embrace.

Nothing can fix our systems except a cultural revolution that dismantles the status quo and brings new thinking into space. What is going to be the character of our leadership? What kind of company do they keep? What is the path to power? In the answers to these questions, the culture around a governance system either nepotistic, corrupt or ethically challenged, is formed.

– Seun Onigbinde is the co-founder and CEO of BudgIT | Twitter:@seunonigbinde | Linkedin: Oluseun Onigbinde.